THE GRAND CANYON BRIDGE

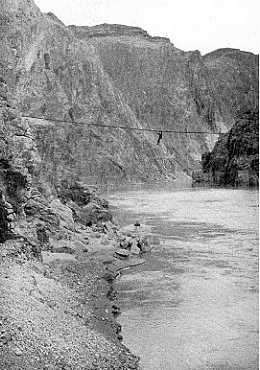

OF THE GRAND CANYON SUSPENSION BRIDGE The completed canyon bridge will be 420 feet along the roadway and is suspended 60 feet above the river in normal flow, but only 13 feet above the rushing torrent when it is at its greatest flood. This is the only bridge across the Colorado above Needles, California, which is 360 miles by river course to the south. The suspension bridge over the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon is practically completed. Late this summer (1921) it will be possible to ride from EI Tovar, on the south rim of the stupendous chasm, to the Kaibab plateau, on the north rim. The bridging of the Granite Gorge of the Colorado opens up a new wonderland in the Grand Canyon National Park. From the Kaibab plateau, which averages. 1,000 feet above the better-known South Rim of the canyon, new and amazing panoramas are presented. Last month I rode down to the river over a trail not yet opened to tourists, messed with the bridge crew, and spent a night in the gorge. The bridge is 11 miles by trail from El Tovar and 4,700 feet below Yaki Point, on the Coconino plateau. The saddle trail, following the Bright Angel and Tonto trails to the river and up Bright Angel Canyon to the Kaibab forest, is about 31 miles in length. Rim-to-rim travelers will spend the night in a camp near Ribbon Falls, about eight miles, beyond the river. It was a chilly morning when we started for the bridge camp. The wind surged through the pines and pinions, and twisted the gnarled cypress trees overlooking the chasm. It is the Rim of the Eternal, to be approached with awe; but people differ. I heard a stout woman, standing by the lookout, say to her daughter, "Oh! Clara, I'm terribly disappointed. We've come at a time of year when there's no water in the canyon." A tall man, with a red face, was explaining to a thin man in a plaid suit that, in contour, the canyon was exactly like the doughnuts his mother used to make.

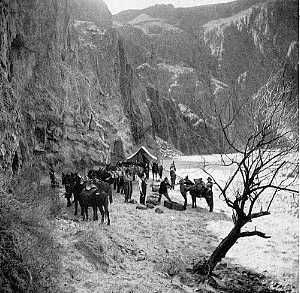

Down we dropped to the Tonto Plateau, the green shelf on the canyon wall lying between the ruby-stained limestone and the gray Archean granite. Here winds a trail of romance. In the shadowy past this was the highway of the Cliff dwellers. Here, in later years, Spaniards whose names are not written on the historic page adventured. There came occasional fir trappers from lands far to the north; the first of those great explorers who dared the descent of the river; hardy miners, whose halfhearted workings still border the Tonto trail. We counted seven wild burros descended from pack animals abandoned by the miners. Deer were recently seen in this part of the canyon. Mountain sheep hide on ledges high up the wall. Many other wild creatures still find refuge in this vast wilderness. The only animals that we saw besides the burros, were wood rats nearly as large as squirrels. These "trade rats" accumulate great mounds of rubbish. From a camp they walk off with the soap and the spoons, leaving pebbles and sticks in exchange. The pack train, carrying the bridge material from railroad to river, made its halfway camp at Pipe Creek. Here only a lonely black kitten greeted us. The pack train was "on the job." It has been a tremendous undertaking to move the lumber, cement, and cables down the 11 miles of steep, winding trail to the bridge site. Many are the exciting tales told by the packers. On one trip a horse went over the cliff, carrying two others with him - but a resourceful lad cut the rope and saved the remainder of the train. Since January these pack trains have been steadily trudging up and down between the hidden river and the railroad on the rim.

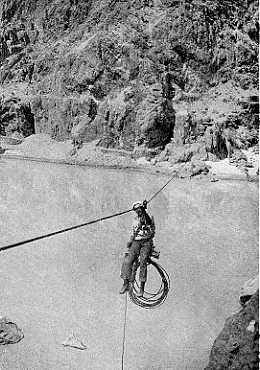

He conceived the idea of "rehearsing" the carrying down of the cables and estimating, with ropes, just the proper length of line necessary between each mule, as the train swung around the curves. The 1,200-pound cable was then loaded on eight mules roped together, with the weight evenly divided, a man walking at the head of each mule.

A 420 FOOT BRIDGE I was fortunate in having the contractor himself explain the project to me. The completed bridge will be 420 feet along the roadways, with a span of 500 feet from center to center of the bearings. The two main steel cables are placed about 10 feet apart and are anchored to the canyon walls 80 feet above the floor level, by means of sections of 80-pound railroad iron set into the rock with concrete. Hanging galvanized steel cables clamped to the main lines above, carry the wood floor of the bridge.

A DEEP, MASTERFUL, SULLEN RIVER When the camp slept and moonlight flooded the gorge, I slipped out of my sleeping bag and walked to the river. The Colorado is a deep, masterful stream, sullen, unfriendly. No habitations border its canyon shores. It has a flow of 20,000 cubic feet per second, reaching a maximum of 200,000 cubic feet. By day its walls take on a strange, reddish-purple glow, but by moonlight they were softly pink. A weird rock, which they call the Temple of Zoroaster, dominated the scene. Jupiter rode high in the heavens. Across the river lay the ruins of an ancient Indian village, its broken stone walls strewn with prehistoric pottery - coils and Greek key patterns - such as are found among the. Mesa Verde cliff dwellings. Perhaps it was never a permanent settlement, only a temporary winter refuge of some peaceful plateau tribe driven down from the heights by the warring Utes. The early chroniclers of the canyon did not mention these Indians. Who will write the long ago romances and tragedies enacted within this mighty gorge? A chill wind swept down the canyon and I crept back into my tent. Next morning, when the ten o'clock sun looked over the cliff, we crossed the river in a canvas boat, rowing well upstream and coming back with the current to the landing beach. The boat leaked. It is difficult to swim the river because of the heavy sand and silt - but in case of an upset one would probably be tossed up on the rocks before reaching the rapids. We climbed the bed of Bright Angel Creek, which here enters the Colorado, to the clump of cottonwoods still called "the Roosevelt camp." Here we discovered the bridge mascot. Little Bright Angel, a gray burro who lives in Elysian Fields, with clear water, plenty of grass, and a carefree life. We fed him pancakes sent by the cook, his favorite dish. There are 113 crossings of the creek on the trail up Bright Angel Canyon to the north rim, and the little burro knows, every one of them. Not long ago he guided the foreman of the bridge crew up to the plateau, showing him just where to cross the stream. I had heard that a distinguished American from Philadelphia, an enthusiast over the Grand Canyon, was to be the first to cross the Grand Canyon bridge; but the foreman told me somewhat confidentially, that Little Bright Angel would be the first fellow across. "You see," he explained, Bright Angel has stood so long on the north shore of the river hoping to get across. He can't swim over, and he doesn't like the canvas boat."

Up in the Kaibab forest, "the island forest," (a great naturalist has called it) live wild animals that have developed on original lines. The Kaibab squirrel and its cousin, the Albert, with their broad feathery tails, are the only American squirrels with conspicuous ear tufts. The herd of deer, variously estimated at from 12,000 to 15,000, are the mule deer, with large, broad ears and rounded, whitish tails, tipped with black. Where there are deer, there are pumas, or mountain lions. They call them cougars in this part of the country. Uncle Jim Owens, an old-timer on the North Rim, has hung out a sign: "Cougars killed to order.” He has a record of 1,100 skins. His cabin walls are covered with them. Other beasts of prey are the big gray timber wolf, the coyote, and the fox. A man who lives here and explores unfrequented cliffs tells me there are antelope on the green shelf under the North Rim. "Uncle Jim" has a promising buffalo herd - 64 in all. Isolated on a promontory and protected, the herd is sure to increase. BACK TO MAIN INDEX | BACK TO VISITOR INFORMATION

|